What Might You Guess About Marks Audience by Reading the Gospel of Mark

Gospel originally meant the Christian message ("the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to exist used as well for the books in which the message was prepare out.[one] In this sense a gospel tin be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words and deeds of Jesus, culminating in his trial and death and concluding with various reports of his post-resurrection appearances.[2] Mod scholars are cautious of relying on the gospels uncritically, but nevertheless, they practice provide a practiced idea of the public career of Jesus, and critical study can attempt to distinguish the original ideas of Jesus from those of the later authors.[3] [iv]

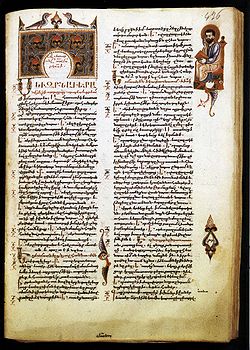

The four canonical gospels were probably written between AD 66 and 110.[5] [half dozen] [7] All four were anonymous (the modern names were added in the 2nd century), almost certainly none were by eyewitnesses, and all are the end-products of long oral and written transmission.[viii] Marking was the commencement to be written, using a diverseness of sources;[ix] [10] the authors of Matthew and Luke, acting independently, used Mark for their narrative of Jesus'southward career, supplementing information technology with the drove of sayings called the Q document and additional cloth unique to each;[11] and there is a virtually-consensus that John had its origins every bit a "signs" source (or gospel) that circulated within a Johannine community.[12] The contradictions and discrepancies between the first 3 and John make information technology incommunicable to have both traditions as as reliable.[thirteen]

Many non-canonical gospels were as well written, all afterwards than the four canonical gospels, and like them advocating the particular theological views of their various authors.[14] [fifteen] Important examples include the Gospel of Thomas, the Gospel of Peter, the Gospel of Judas, the Gospel of Mary, infancy gospels such as the Gospel of James (the first to introduce the perpetual virginity of Mary), and gospel harmonies such as the Diatessaron.

Etymology [edit]

Gospel is the Old English translation of Greek εὐαγγέλιον , meaning "good news";[16] this may be seen from analysis of ευαγγέλιον ( εὖ "adept" + ἄγγελος "messenger" + -ιον diminutive suffix). The Greek term was Latinized as evangelium in the Vulgate, and translated into Latin equally bona annuntiatio . In Sometime English, it was translated as gōdspel ( gōd "skillful" + spel "news"). The Old English language term was retained as gospel in Eye English language Bible translations and hence remains in use also in Modern English.

Canonical gospels [edit]

Contents [edit]

The four approved gospels are the gospel of Matthew, the gospel of Mark, the gospel of Luke and the gospel of John. They share the same basic outline of the life of Jesus: he begins his public ministry in conjunction with that of John the Baptist, calls disciples, teaches and heals and confronts the Pharisees, dies on the cross, and is raised from the dead.[17]

Each has its own distinctive agreement of him and his divine function[15] and scholars recognize that the differences of detail between the gospels are irreconcilable, and any attempt to harmonize them would only disrupt their distinct theological messages.[18]

Mark never calls him "God" or claims that he existed prior to his earthly life, apparently believes that he had a normal man parentage and birth, makes no endeavour to trace his beginnings dorsum to Male monarch David or Adam, and originally had no mail-resurrection appearances,[19] [20] although Marking 16:7, in which the boyfriend discovered in the tomb instructs the women to tell "the disciples and Peter" that Jesus will come across them again in Galilee, hints that the writer knew of the tradition.[21]

Matthew and Luke base of operations their narratives of the life of Jesus on that in Mark, but each makes subtle changes, Matthew stressing Jesus's divine nature – for case, the "immature man" who appears at Jesus' tomb in Mark becomes a radiant affections in Matthew.[22] [23] Similarly, the miracle stories in Mark confirm Jesus' status as an emissary of God (which was Mark'south understanding of the Messiah), but in Matthew they demonstrate divinity.[24]

Luke, while following Mark's plot more than faithfully than does Matthew, has expanded on the source, corrected Mark'south grammer and syntax, and eliminated some passages entirely, notably most of chapters half dozen and 7.[25] John, the virtually overtly theological, is the first to make Christological judgements exterior the context of the narrative of Jesus's life.[fifteen]

Matthew, Mark and Luke are termed the synoptic gospels considering they present very like accounts of the life of Jesus while John presents a significantly different flick of Jesus's career,[26] omitting whatever mention of his beginnings, nativity and childhood, his baptism, temptation and transfiguration.[26] John'southward chronology and arrangement of incidents is also distinctly different, clearly describing the passage of three years in Jesus's ministry building in contrast to the single year of the synoptics, placing the cleansing of the Temple at the beginning rather than at the stop, and the Last Supper on the mean solar day before Passover instead of beingness a Passover meal.[27] The Gospel of John is the simply gospel to call Jesus God. In dissimilarity to Mark, where Jesus hides his identity as messiah, in John he openly proclaims it.[28]

Composition [edit]

The Synoptic sources: the Gospel of Marker (the triple tradition), Q (the double tradition), and material unique to Matthew (the M source), Luke (the L source), and Mark[29]

Like the rest of the New Testament, the four gospels were written in Greek.[xxx] The Gospel of Mark probably dates from c. Advertizing 66–seventy,[5] Matthew and Luke around Advertising 85–ninety,[vi] and John AD 90–110.[7] Despite the traditional ascriptions, all four are anonymous and most scholars concord that none were written by eyewitnesses.[8] A few conservative scholars defend the traditional ascriptions or attributions, but for a variety of reasons the majority of scholars take abandoned this view or hold it only tenuously.[31]

In the immediate aftermath of Jesus' decease his followers expected him to return at any moment, certainly within their own lifetimes, and in consequence in that location was fiddling motivation to write anything down for future generations, merely every bit eyewitnesses began to die, and as the missionary needs of the church grew, there was an increasing demand and need for written versions of the founder's life and teachings.[32] The stages of this process can be summarised equally follows:[33]

- Oral traditions – stories and sayings passed on largely every bit separate self-independent units, not in whatever order;

- Written collections of phenomenon stories, parables, sayings, etc., with oral tradition continuing aslope these;

- Written proto-gospels preceding and serving every bit sources for the gospels – the dedicatory preface of Luke, for case, testifies to the beingness of previous accounts of the life of Jesus.[34]

- Gospels formed by combining proto-gospels, written collections and still-electric current oral tradition.

Marker is generally agreed to be the first gospel;[9] it uses a variety of sources, including conflict stories (Mark ii:1–3:6), apocalyptic soapbox (4:1–35), and collections of sayings, although not the sayings gospel known equally the Gospel of Thomas and probably not the Q source used by Matthew and Luke.[10] The authors of Matthew and Luke, acting independently, used Marking for their narrative of Jesus'southward career, supplementing it with the collection of sayings called the Q document and boosted material unique to each called the 1000 source (Matthew) and the Fifty source (Luke).[11] [note 1] Mark, Matthew and Luke are called the synoptic gospels considering of the shut similarities betwixt them in terms of content, arrangement, and linguistic communication.[35] The authors and editors of John may have known the synoptics, simply did not use them in the way that Matthew and Luke used Mark.[36] There is a near-consensus that this gospel had its origins equally a "signs" source (or gospel) that circulated within the Johannine customs (the community that produced John and the 3 epistles associated with the name), later expanded with a Passion narrative and a serial of discourses.[12] [note 2]

All 4 too apply the Jewish scriptures, by quoting or referencing passages, or by interpreting texts, or past alluding to or echoing biblical themes.[38] Such use can be extensive: Mark'due south description of the Parousia (2nd coming) is made upwardly almost entirely of quotations from scripture.[39] Matthew is full of quotations and allusions,[forty] and although John uses scripture in a far less explicit fashion, its influence is notwithstanding pervasive.[41] Their source was the Greek version of the scriptures, called the Septuagint – they do non seem familiar with the original Hebrew.[42]

Genre and historical reliability [edit]

The consensus amidst modern scholars is that the gospels are a subset of the ancient genre of bios, or aboriginal biography.[43] Ancient biographies were concerned with providing examples for readers to emulate while preserving and promoting the field of study's reputation and retentiveness; the gospels were never simply biographical, they were propaganda and kerygma (preaching).[44] As such, they present the Christian message of the second half of the first century Advertizement,[45] and as Luke's try to link the birth of Jesus to the census of Quirinius demonstrates, there is no guarantee that the gospels are historically accurate.[46]

The majority view amongst critical scholars is that the authors of Matthew and Luke take based their narratives on Mark's gospel, editing him to adjust their own ends, and the contradictions and discrepancies between these three and John go far impossible to have both traditions as equally reliable.[thirteen] In add-on, the gospels nosotros read today have been edited and corrupted over time, leading Origen to mutter in the 3rd century that "the differences among manuscripts take become keen, ... [considering copyists] either neglect to check over what they accept transcribed, or, in the process of checking, they make additions or deletions as they please".[47] Most of these are insignificant, but many are significant,[48] an example beingness Matthew 1:18, altered to imply the pre-beingness of Jesus.[49] For these reasons modern scholars are cautious of relying on the gospels uncritically, but still they practise provide a adept thought of the public career of Jesus, and critical written report can attempt to distinguish the original ideas of Jesus from those of the later authors.[3] [iv]

Scholars usually concord that John is not without historical value: certain of its sayings are as old or older than their synoptic counterparts, its representation of the topography around Jerusalem is often superior to that of the synoptics, its testimony that Jesus was executed before, rather than on, Passover, might well be more than accurate, and its presentation of Jesus in the garden and the prior meeting held past the Jewish authorities are possibly more than historically plausible than their synoptic parallels.[50] Still, it is highly unlikely that the writer had straight knowledge of events, or that his mentions of the Dear Disciple as his source should be taken as a guarantee of his reliability.[51]

Textual history and canonisation [edit]

The oldest gospel text known is 𝔓52 , a fragment of John dating from the start one-half of the 2nd century.[52] The creation of a Christian canon was probably a response to the career of the heretic Marcion (c. 85–160), who established a catechism of his ain with just i gospel, the gospel of Luke, which he edited to fit his own theology.[53] The Muratorian catechism, the earliest surviving list of books considered (by its own author at least) to form Christian scripture, included Matthew, Marking, Luke and John. Irenaeus of Lyons went further, stating that there must be iv gospels and only four considering there were four corners of the World and thus the Church should accept four pillars.[1] [54]

Non-canonical (apocryphal) gospels [edit]

The many apocryphal gospels arose from the 1st century onward, frequently under causeless names to heighten their brownie and authorisation, and often from within branches of Christianity that were eventually branded heretical.[55] They can exist broadly organised into the following categories:[56]

- Infancy gospels: arose in the 2nd century, include the Gospel of James, as well called the Protoevangelium, which was the showtime to introduce the concept of the Perpetual Virginity of Mary, and the Infancy Gospel of Thomas (not to be confused with the unrelated Coptic Gospel of Thomas), both of which related many miraculous incidents from the life of Mary and the childhood of Jesus that are not included in the approved gospels.

- Ministry building gospels

- Sayings gospels and agrapha

- Passion, resurrection and post-resurrection gospels

- Gospel harmonies: in which the four approved gospels are combined into a unmarried narrative, either to present a consistent text or to produce a more than accessible account of Jesus' life.

The counterfeit gospels can also be seen in terms of the communities which produced them:

- The Jewish-Christian gospels are the products of Christians of Jewish origin who had not given upwardly their Jewish identity: they regarded Jesus as the messiah of the Jewish scripture, just did not agree that he was God, an idea which, although fundamental to Christianity every bit it eventually developed, is contrary to Jewish beliefs.

- Gnostic gospels uphold the idea that the universe is the product of a hierarchy of gods, of whom the Jewish god is a rather low-ranking fellow member. Gnosticism holds that Jesus was entirely "spirit", and that his earthly life and expiry were therefore only an advent, not a reality. Many Gnostic texts deal not in concepts of sin and repentance, just with illusion and enlightenment.[57]

| Title | Probable date | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Epistle of the Apostles | Mid 2nd c. | Anti-gnostic dialogue betwixt Jesus and the disciples after the resurrection, emphasising the reality of the flesh and of Jesus' fleshly resurrection |

| Gospel According to the Hebrews | Early second c. | Events in the life of Jesus; Jewish-Christian, with possible gnostic overtones |

| Gospel of the Ebionites | Early 2nd c. | Jewish-Christian, embodying anti-sacrificial concerns |

| Gospel of the Egyptians | Early 2nd c. | "Salome" figures prominently; Jewish-Christian stressing asceticism |

| Gospel of Mary | 2nd c. | Dialogue of Mary Magdalene with the apostles, and her vision of Jesus' secret teachings. It was originally written in Greek and is often interpreted as a Gnostic text. Information technology is typically not considered a gospel by scholars since it does not focus on the life of Jesus.[59] |

| Gospel of the Nazareans | Early on 2d c. | Aramaic version of Matthew, possibly lacking the beginning 2 chapters; Jewish-Christian |

| Gospel of Nicodemus | 5th c. | Jesus' trial, crucifixion and descent into Hell |

| Gospel of Peter | Early 2nd c. | Bitty narrative of Jesus' trial, death and emergence from the tomb. It seems to be hostile toward Jews, and includes docetic elements.[60] It is a narrative gospel and is notable for asserting that Herod, non Pontius Pilate, ordered the crucifixion of Jesus. It had been lost but was rediscovered in the 19th century.[60] |

| Gospel of Philip | 3rd c. | Mystical reflections of the disciple Philip |

| Gospel of the Saviour | Tardily 2nd c. | Fragmentary business relationship of Jesus' last hours |

| Coptic Gospel of Thomas | Early 2nd c. | The Oxford Lexicon of the Christian Church says that the original may date from c. 150.[61] Some scholars believe that it may represent a tradition independent from the canonical gospels, but that developed over a long time and was influenced by Matthew and Luke;[61] other scholars believe it is a later text, dependent from the approved gospels.[62] [63] While it can exist understood in Gnostic terms, it lacks the characteristic features of Gnostic doctrine.[61] It includes two unique parables, the parable of the empty jar and the parable of the assassin.[64] It had been lost just was discovered, in a Coptic version dating from c. 350, at Nag Hammadi in 1945–46, and 3 papyri, dated to c. 200, which comprise fragments of a Greek text similar to but not identical with that in the Coptic language, have also been found.[61] |

| Infancy Gospel of Thomas | Early 2d c. | Miraculous deeds of Jesus between the ages of v and twelve |

| Gospel of Truth | Mid 2nd c. | Joys of Salvation |

| Papyrus Egerton 2 | Early second c. | Bitty, 4 episodes from the life of Jesus |

| Diatessaron | Late 2nd c. | Gospel harmony (and the offset such gospel harmony) equanimous past Tatian; may have been intended to replace the carve up gospels as an authoritative text. It was accepted for liturgical purposes for as much every bit two centuries in Syrian arab republic, only was eventually suppressed.[65] [66] }} |

| Protoevangelium of James | Mid 2d c. | Birth and early life of Mary, and birth of Jesus |

| Gospel of Marcion | Mid 2d c. | Marcion of Sinope, c. 150, had a much shorter version of the gospel of Luke, differing substantially from what has now become the standard text of the gospel and far less oriented towards the Jewish scriptures. Marcion's critics said that he had edited out the portions of Luke he did not similar, though Marcion argued that his was the more genuinely original text. He is said to have rejected all other gospels, including those of Matthew, Mark and especially John, which he alleged had been forged past Irenaeus. |

| Undercover Gospel of Marking | Uncertain | Allegedly a longer version of Mark written for an elect audition |

| Gospel of Judas | Tardily 2nd c. | Purports to tell the story of the gospel from the perspective of Judas, the disciple who is normally said to have betrayed Jesus. It paints an unusual motion-picture show of the relationship between Jesus and Judas, in that information technology appears to translate Judas'southward act not as expose, simply rather as an act of obedience to the instructions of Jesus. The text was recovered from a cave in Egypt by a thief and thereafter sold on the black market until it was finally discovered past a collector who, with the assistance of academics from Yale and Princeton, was able to verify its authenticity. The document itself does not claim to have been authored by Judas (it is, rather, a gospel about Judas), and is known to date to at least 180 Advertisement.[67] |

| Gospel of Barnabas | 14th–16th c. | Contradicts the ministry building of Jesus in canonical New Testament and strongly denies Pauline doctrine, but has clear parallels with Islam, mentioning Muhammad as Messenger of God. Jesus identifies himself as a prophet, not the son of God.[68] |

See besides [edit]

- Agrapha

- Apocalyptic literature

- The Aquarian Gospel of Jesus the Christ

- Authorship of the Bible

- Bodmer Papyri

- Dating the Bible

- Fifth gospel (genre)

- The gospel

- Gospel (liturgy)

- Gospel harmony

- Gospel in Islam

- Gospel of Marcion

- Jesusism

- Jewish-Christian gospels

Notes [edit]

- ^ The priority of Mark is accepted by virtually scholars, but there are important dissenting opinions: see the commodity Synoptic problem.

- ^ The debate over the composition of John is too complex to be treated adequately in a single paragraph; for a more than nuanced view run into Aune (1987), "Gospel of John".[37]

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ a b Cross & Livingstone 2005, p. 697.

- ^ Alexander 2006, p. 16.

- ^ a b Cerise 2011, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b Sanders 1995, pp. 4–5.

- ^ a b Perkins 1998, p. 241.

- ^ a b Reddish 2011, pp. 108, 144.

- ^ a b Lincoln 2005, p. 18.

- ^ a b Cherry 2011, pp. 13, 42.

- ^ a b Goodacre 2001, p. 56.

- ^ a b Boring 2006, pp. xiii–14.

- ^ a b Levine 2009, p. 6.

- ^ a b Burge 2014, p. 309.

- ^ a b Tuckett 2000, p. 523.

- ^ Petersen 2010, p. 51.

- ^ a b c Culpepper 1999, p. 66.

- ^ Woodhead 2004, p. 4.

- ^ Thompson 2006, p. 183.

- ^ Scholz 2009, p. 192.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 158.

- ^ Parker 1997, p. 125.

- ^ Telford 1999, p. 149.

- ^ Beaton 2005, pp. 117, 123.

- ^ Morris 1986, p. 114.

- ^ Aune 1987, p. 59.

- ^ Johnson 2010a, p. 48.

- ^ a b Burkett 2002, p. 217.

- ^ Anderson 2011, p. 52.

- ^ Burkett 2002, p. 214.

- ^ Honoré 1986, pp. 95–147.

- ^ Porter 2006, p. 185.

- ^ Lindars, Edwards & Court 2000, p. 41.

- ^ Ruddy 2011, p. 17.

- ^ Burkett 2002, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Martens 2004, p. 100.

- ^ Goodacre 2001, p. one.

- ^ Perkins 2012, p.[ page needed ].

- ^ Aune 1987, pp. 243–245.

- ^ Allen 2013, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Edwards 2002, p. 403.

- ^ Beaton 2005, p. 122.

- ^ Lieu 2005, p. 175.

- ^ Allen 2013, p. 45.

- ^ Lincoln 2004, p. 133.

- ^ Dunn 2005, p. 174.

- ^ Keith & Le Donne 2012, p.[ folio needed ].

- ^ Reddish 2011, p. 22.

- ^ Ehrman 2005a, pp. vii, 52.

- ^ Ehrman 2005a, p. 69.

- ^ Ehrman 1996, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Theissen & Merz 1998, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Lincoln 2005, p. 26.

- ^ Fant & Reddish 2008, p. 415.

- ^ Ehrman 2005a, p. 34.

- ^ Ehrman 2005a, p. 35.

- ^ Aune 2003, pp. 199–200.

- ^ Ehrman & Plese 2011, p. passim.

- ^ Pagels 1989, p. 20.

- ^ Ehrman 2005b, pp. xi–xii.

- ^ Bernhard 2006, p. two.

- ^ a b Cross & Livingstone 2005, "Gospel of St. Peter".

- ^ a b c d Cross & Livingstone 2005, "Gospel of Thomas".

- ^ Casey 2010, p.[ folio needed ].

- ^ Meier 1991, p.[ page needed ].

- ^ Funk, Hoover & Jesus Seminar 1993, "The Gospel of Thomas".

- ^ Metzger 2003, p. 117.

- ^ Gamble 1985, pp. 30–35.

- ^ Ehrman 2006, p. passim.

- ^ Wiegers 1995.

Bibliography [edit]

- Achtemeier, Paul J. (1985). HarperCollins Bible Dictionary. San Francisco: HarperCollins. ISBN9780060600372.

- Alexander, Loveday (2006). "What is a Gospel?". In Barton, Stephen C. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Gospels. Cambridge University Press. ISBN9780521807661.

- Allen, O. Wesley (2013). Reading the Synoptic Gospels. Chalice Press. ISBN978-0827232273.

- Anderson, Paul N. (2011). The Riddles of the Fourth Gospel: An Introduction to John. Fortress Printing. ISBN978-1451415551.

- Aune, David E. (1987). The New Testament in its literary environment. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN978-0-664-25018-eight.

- Aune, David E. (2003). The Westminster Dictionary of New Testament and Early on Christian Literature and Rhetoric. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN978-0-664-25018-8.

- Bauckham, Richard (2008). Jesus and the Eyewitnesses: The Gospels as Eyewitness Testimony. Eerdmans. ISBN978-0802863904.

- Beaton, Richard C. (2005). "How Matthew Writes". In Bockmuehl, Markus; Hagner, Donald A. (eds.). The Written Gospel. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-521-83285-4.

- Bernhard, Andrew East. (2006). Other Early Christian Gospels: A Critical Edition of the Surviving Greek Manuscripts. Library of New Attestation Studies. Vol. 315. London; New York: T & T Clark. ISBN0-567-04204-nine.

- Boring, M. Eugene (2006). Mark: A Commentary. Presbyterian Publishing Corp. ISBN978-0-664-22107-ii.

- Brownish, Raymond E. (1966). The Gospel co-ordinate to John (I–XII): Introduction, Translation, and Notes, vol. 29, Anchor Yale Bible. Yale University Printing. ISBN9780385015172.

- Burge, Gary One thousand. (2014). "Gospel of John". In Evans, Craig A. (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Routledge. ISBN978-1317722243.

- Burkett, Delbert (2002). An introduction to the New Testament and the origins of Christianity. Cambridge University Press. ISBN978-0-521-00720-7.

- Burridge, R.A. (2006). "Gospels". In Rogerson, J.Due west.; Lieu, Judith M. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0199254255.

- Casey, Maurice (2010). Jesus of Nazareth: An Independent Historian'due south Account of His Life and Teaching. T&T Clark. ISBN978-0-567-64517-3.

- Charlesworth, James H. (2008). The Historical Jesus: An Essential Guide. Abingdon Press. ISBN978-0687021673.

- Cross, Frank Leslie; Livingstone, Elizabeth A. (2005). The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0192802903.

- Culpepper, R. Alan (1999). "The Christology of the Johannine Writings". In Kingsbury, Jack Dean; Powell, Mark Allan Powell; Bauer, David R. (eds.). Who Do You Say that I Am?: Essays on Christology. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN9780664257521.

- Donahue, John (2005). The Gospel of Marking. Liturgical Printing. ISBN978-0814659656.

- Duling, Dennis C. (2010). "The Gospel of Matthew". In Aune, David East. (ed.). The Blackwell Companion to the New Testament. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN978-1444318944.

- Dunn, James D.Yard. (2005). "The Tradition". In Dunn, James D.M.; McKnight, Scot (eds.). The Historical Jesus in Recent Research. Eisenbrauns. ISBN978-1575061009.

- Edwards, James R. (2015). The Gospel according to Luke. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN978-0802837356.

- Edwards, James R. (2002). The Gospel co-ordinate to Mark. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN978-0851117782.

- Ehrman, Bart; Plese, Zlatko (2011). The Counterfeit Gospels: Texts and Translations. Oxford Academy Press. ISBN9780199831289.

- Ehrman, Bart (2006). The Lost Gospel of Judas Iscariot. Oxford University Press. ISBN9780199831289.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2005a). Misquoting Jesus. Harper Collins.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2005b). Lost Christianities. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0195182491.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1999). Jesus: Apocalyptic Prophet of the New Millennium. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0199839438.

- Ehrman, Bart D. (1996). The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture: The Effect of Early on Christological Controversies on the Text of the New Testament. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-xix-976357-3.

- Fant, Clyde E.; Reddish, Mitchell E. (2008). Lost Treasures of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN9780802828811.

- Funk, Robert Due west.; Hoover, Roy W.; Jesus Seminar (1993). "The Gospel of Thomas". The v gospels. HarperSanFrancisco. pp. 471–532.

- Gabel, John; et al. (1996). The Bible as Literature. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-19-509285-1.

- Risk, Harry (1985). The New Testament Canon: Its Making and Pregnant. Fortress Press. ISBN978-0-8006-0470-seven.

- Gerhardsson, Birger (1998). Retention and Manuscript: Oral Tradition and Written Transmission in Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity. Eerdmans. ISBN9780802843661.

- Goodacre, Mark (2001). The Synoptic Problem: A Way Through the Maze. A&C Blackness. ISBN978-0567080561.

- Harrington, Daniel J. (1991). The Gospel of Matthew. Liturgical Printing. ISBN978-0814658031.

- Hatina, Thomas R. (2014). "Gospel of Marking". In Evans, Craig A. (ed.). Routledge Encyclopedia of the Historical Jesus. Routledge. ISBN978-1317722243.

- Hengel, Martin (2003). Studies in the Gospel of Mark. Fortress Printing. ISBN978-1592441884.

- Honoré, A.M. (1986). "A statistical study of the synoptic problem". Novum Testamentum. ten (ii/3): 95–147. doi:10.2307/1560364. JSTOR 1560364.

- Hurtado, Larry W. (2005). Lord Jesus Christ: Devotion to Jesus in Earliest Christianity. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN978-0802831675.

- Johnson, Luke Timothy (2010a). The Writings of the New Attestation – An Interpretation (3rd ed.). Fortress Printing. ISBN978-1451413281.

- Johnson, Luke Timothy (2010b). The New Testament: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford Academy Press. ISBN978-0199745999.

- Keith, Chris; Le Donne, Anthony, eds. (2012). Jesus, Criteria, and the Demise of Authenticity. T&T Clark. ISBN9780567691200.

- Levine, Amy-Jill (2009). "Introduction". In Levine, Amy-Jill; Allison, Dale C. Jr.; Crossan, John Dominic (eds.). The Historical Jesus in Context. Princeton University Press. ISBN978-1400827374.

- Lieu, Judith (2005). "How John Writes". In Bockmuehl, Markus; Hagner, Donald A. (eds.). The Written Gospel. Oxford Academy Printing. ISBN978-0-521-83285-4.

- Lincoln, Andrew (2004). "Reading John". In Porter, Stanley E. (ed.). Reading the Gospels Today. Eerdmans. ISBN978-0802805171.

- Lincoln, Andrew (2005). Gospel Co-ordinate to St John. Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN978-1441188229.

- Lindars, Barnabas; Edwards, Ruth; Courtroom, John Thou. (2000). The Johannine Literature. A&C Black. ISBN978-ane-84127-081-iv.

- Martens, Allan (2004). "Conservancy Today: Reading Luke's Message for a Gentile Audience". In Porter, Stanley E. (ed.). Reading the Gospels Today. Eerdmans. ISBN978-0802805171.

- Mckenzie, John L. (1995). The Dictionary of the Bible. Simon and Schuster. ISBN978-0684819136.

- McMahon, Christopher (2008). "Introduction to the Gospels and Acts of the Apostles". In Ruff, Jerry (ed.). Agreement the Bible: A Guide to Reading the Scriptures. Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN978-0884898528.

- McNichol, Allan J. (2000). "Gospel, Adept News". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Lexicon of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN978-9053565032.

- Meier, John P. (1991). A Marginal Jew. Book 1: The roots of the trouble and the person. Doubleday. ISBN978-0-385-26425-ix.

- Metzger, Bruce (2003). The New Testament: Its Groundwork, Growth, and Content. Abingdon. ISBN978-068-705-2639.

- Morris, Leon (1986). New Testament Theology. Zondervan. ISBN978-0-310-45571-four.

- Nolland, John (2005). The Gospel of Matthew: A Commentary on the Greek Text. Eerdmans.

- O'Day, Gail R. (1998). "John". In Newsom, Carol Ann; Ringe, Sharon H. (eds.). Women's Bible Commentary. Westminster John Knox. ISBN978-0281072606.

- Pagels, Elaine (1989). The Gnostic Gospels (PDF). Random Business firm.

- Parker, D.C. (1997). The Living Text of the Gospels. Cambridge University Printing. ISBN978-0521599511.

- Perkins, Pheme (1998). "The Synoptic Gospels and the Acts of the Apostles: Telling the Christian Story". In Barton, John (ed.). The Cambridge companion to biblical estimation. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN978-0-521-48593-7.

- Perkins, Pheme (2009). Introduction to the Synoptic Gospels. Eerdmans. ISBN978-0802865533.

- Perkins, Pheme (2012). Reading the New Attestation: An Introduction. Paulist Press. ISBN978-0809147861.

- Petersen, William 50. (2010). "The Diatessaron and the Fourfold Gospel". In Horton, Charles (ed.). The Earliest Gospels. Bloomsbury. ISBN9780567000972.

- Porter, Stanley Due east. (2006). "Linguistic communication and Translation of the New Testament". In Rogerson, J.Westward.; Lieu, Judith M. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Biblical Studies. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0199254255.

- Porter, Stanley Eastward.; Fay, Ron C. (2018), The Gospel of John in Modern Interpretation, Kregel Academic

- Powell, Mark Allan (1998). Jesus every bit a Figure in History: How Modern Historians View the Man from Galilee. Eerdmans. ISBN978-0-664-25703-three.

- Reddish, Mitchell (2011). An Introduction to The Gospels. Abingdon Press. ISBN978-1426750083.

- Riesner, Rainer (1988). Jesus als Lehrer: Eine Untersuchung zum Ursprung der Evangelien-Überlieferung. J. C. B. Mohr. ISBN9783161451959.

- Sanders, E.P. (1995). The Historical Figure of Jesus. Penguin. ISBN9780141928227.

- Vielhauer, Philipp; Strecker, Georg (2005). "Jewish-Christian Gospels". In Schneemelcher, Wilhelm (ed.). New Testament Apocrypha. Vol. ane. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN9780664227210.

- Senior, Donald (1996). What are they proverb about Matthew?. Paulist Press. ISBN978-0-8091-3624-7.

- Scholz, Daniel J. (2009). Jesus in the Gospels and Acts: Introducing the New Testament. Saint Mary's Printing. ISBN9780884899556.

- Telford, W.R. (1999). The Theology of the Gospel of Mark. Cambridge Academy Press. ISBN978-0521439770.

- Theissen, Gerd; Merz, Annette (1998) [1996]. The Historical Jesus: A Comprehensive Guide. Fortress Press. ISBN978-one-4514-0863-8.

- Thompson, Marianne (2006). "Gospel of John". In Barton, Stephen C. (ed.). The Cambridge Companion to the Gospels. Cambridge University Press. ISBN9780521807661.

- Tuckett, Christopher (2000). "Gospel, Gospels". In Freedman, David Noel; Myers, Allen C. (eds.). Eerdmans Dictionary of the Bible. Eerdmans. ISBN978-9053565032.

- Wiegers, K. (1995). "Muhammad as the Messiah: A comparison of the polemical works of Juan Alonso with the Gospel of Barnabas". Biblitheca Orientalis: 245–291.

- Woodhead, Linda (2004). Christianity: A Very Brusk Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0199687749.

External links [edit]

![]() Quotations related to Gospel at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Gospel at Wikiquote

- A detailed word of the textual variants in the gospels – covering about 1200 variants on 2000 pages.

- Greek New Attestation – the Greek text of the New Testament: specifically the Westcott-Hort text from 1881, combined with the NA26/27 variants.

- Synoptic Parallels A spider web tool for finding corresponding passages in the Gospels

mitchellwhady1951.blogspot.com

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gospel

0 Response to "What Might You Guess About Marks Audience by Reading the Gospel of Mark"

Postar um comentário